News & Blog

CIL2: Alternative Uses and the effect of Time on Supply

Posted on February 07, 2013

In the previous article we discussed the fixed supply of land. This article discusses the impact of changing land uses and the effect of time on the supply of land for development.

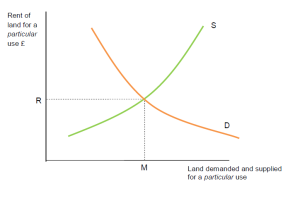

The total land mass of a Local Authority area could be considered to be in fixed supply, however, land is not in fixed supply from the viewpoint of any one use. The use of land in the UK is informed by the economics of the property market and is governed by planning policy. If demand for a particular land use is high, developers will seek to buy land with a lower existing use value for redevelopment to the higher value use. This will occur if the proposed new use has a higher residual land value than the existing use less the total costs of redevelopment including CIL/S106. In short the higher the demand, the greater the price, the more land will usually be supplied for that particularly use i.e. there will be an upward-sloping supply curve on our Supply and Demand chart. See figure 1.

Figure 1

But of course land is not homogeneous. In practice land varies in quality. It has different locational characteristics, accessibility and physical conditions. It also has different town planning status and is sometimes restricted by covenants. These factors give rise to differential land values.

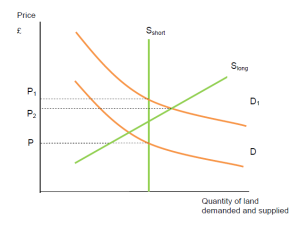

Also changes in land supply to a different use normally take time to come through the planning and development pipeline. For example, it takes considerable time for urban extension land to be (say) adequately master-planned; released from Green Belt; receive planning permission; before building can commence.

The effect of this timescale is illustrated on figure 2. Price jumps up in the short term from P to P1; but as supply increases the price pressure reduces (P2).

Figure 2

This is a very theoretical approach. In reality the property market is not a perfect market. The time taken to achieve the “S-long” position (in figure 2) varies considerably and it may never reach equilibrium. Developers respond to the price signals from purchasers and investors (notably during the last boom in city living apartments), bidding up the price of land. However, the time it takes to allocate sites could itself contribute to rising land prices (as in greenfield residential sites). Contrast this with the oversupply of previously developed industrial land in certain parts of the north and the midlands where values are low due to low demand.

Finally, this simple supply and demand model in determining value/price does not make any allowance for the size of the ‘stock’ of existing properties relative to the ‘flow’ of new property coming on to the market. This is a key aspect which will be discussed further in the next article.